The earliest known fossils of edentates are from the late Paleocene and early Eocene. The first South American xenarthran fossil, Utaetus, a primitive armadillo, was from the late Paleocene epoch, roughly 60 million years ago (Britannica). Early edentates are thought to be generally unspecialized herbivores that inha bited scrubby savannas. It is thought that their extinction is due to the evolu tion of more specialized edentates which occupy a narrower ecological niche. Th is left little space for the less specialized edentates, which eventually went e xtinct (Dickson in MacDonald 1984: 770).

In the Tertiary period, edentates of South America radiated into three infraorde rs: Loricata, Vermilingua, and Pilosa. The infraorder Loricata includes the Das ypodidae (armadillos) and their extinct relatives, the Glyptodontidae (so-called turtle armadillos), as well as the Peltiphilidae.

|

|

Living xenarthrans : On the left, a sloth. At right, a hairy armadillo from Santa Cruz, Argentina.

All xenarthrans are descended from the family Dasypodidae, which are characteriz ed by the top and sides of the body covered with horny scutes over a bony, flexi ble carapace. This family comprises four subfamilies, the Dasypodinae, the Stego theriinae, the Pampatheriinae, and the Chlamyphorinae. Dasypodinae consists of the living armadillos as well as Utaetus, found during the lower Eocene to the R ecent. The fossils of Dasypodinae vary in size, some being as small as a modern armadillo. Others, like the South American Pliocene Macroeuphractus had a skul l nearly 28 cm (11 in.) long. Its head and body were almost 2 m long (6.6 ft.). The Dasypodinae had a mostly invertebrate diet, but also ate carrion and some plants. Fossils from the extinct Stegotheriinae subfamily are from the lower Mi ocene in South America. Its members had elongated anteater-like skulls with muc h reduced cylindrical cheek teeth, and were highly specialized for an insectivor ous diet. Fossils of the Pampatheriinae are from the late Miocene to the Pleist ocene and are characterized by great size. A nearly complete skeleton of Pampat herium found in Texas was the size of a rhinoceros. Pampatheriinae had an herbi vorous diet. Chlamyphorinae consists of the living genera Chlamyphorus and Burm eisteria.

The extinct family Glyptodontidae are distinguished from the Dasypodidae by the possession of a rigid turtle-like carapace. They appear in the fossil record fr om the Eocene to the late Pleistocene in South and North America. Glyptodonts h ad moved into North America by the Pleistocene, and gradually increased in size throughout their history, increasing to a length of 5 m (16.5 in.) with a rigid 3 m (10 ft.) shell on its back (Britannica). The other extinct relative of the armadillo is the family Peltephilidae, which are found during the upper Oligocen e to lower Pliocene in South America. They had short, broad skulls, possessed h orn-like structures on the head armor, and were specialized for flesh eating, pr obably as predators.

In addition to the infraorder Loricata (which comprises armadillos), the second infraorder Vermilingua consists of the anteaters. There is a spotty fossil reco rd of this infraorder; none have been found any earlier than the Miocene (Dickso n in MacDonald(ed.) 1984: 772). Fossils of the family Myrmecophagidae, are toot hless and appear to have adapted to an insectivorous diet. They first appeared in South America in the early Miocene and recently have spread into Central Amer ica.

The third infraorder Pilosa includes the living tree sloths (Bradypodidae) and t he ground sloths (families Megatheriidae, Megalonychidae, Mylodontidae, and Orop hodontidae). There are no known fossils of Bradypodidae, but they inhabit South and Central America. The oldest fossils of ground sloths are of the family Meg atheriidae, found in Oligocene deposits in South America. In the late Miocene, ground sloths began to spread from South America to the West Indies and southern North America, possibly by rafting across sea barriers as waif immigrants. The y have a partial development of upper canines and a spout-like terminus on the l ower jaw. Megatheriidae were generally of small size, roughly 1.3 m (4.5 ft.) i n length. The Pleistocene Megatherium was a massive ground sloth larger than an elephant.

|

|

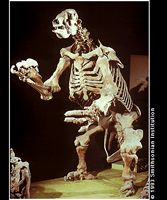

Giant sloth : Above at left, the skull of Glossotherium harlani, a giant ground sloth that roamed southern California in the Pleistocene. At right, a mounted skeleton of a giant ground sloth.

Three additional families of giant ground sloths appeared in the late Oligocene, some as large as modern elephants. The Megalonychidae family is found in North America and the West Indies in the Pleistocene. Large canine-like teeth and th e absence of a spout-like terminus on the lower jaw characterize the megalonychi ds, which ranged in size from that of a small domestic cat to that of an ox. Ma jor fossils groups in the family Megalonychidae include six fossil genera in the subfamily Ortotherinae and 16 fossil genera in the subfamily Megalonychinae. T he family Mylodontidae were present in South America and the southwestern United States during the Pleistocene, and are distinguished by the partial development of the upper canines, triangular-shaped teeth, and a hindfoot with the first to e reduced. The mylodonts were very large and awkward, following the trend of th e other ground sloth families. For example, the Pleistocene Glossotherium was t he size of a large ox. The family Orophodintidae lived during the Oligocene in South America. Some distinguishing features of these small sloths are highly specialized ankle bones.